On Wednesday night, I spent the evening at the The Royal Opera Stores at Abercwmboi near Aberdare in South Wales. Not usually open to the public, the stores (used because it is cheaper to store the props here than in London) are described by Dylan Moore, in his review for the ArtsDesk as “a hangar-sized warehouse on an industrial park overlooked by the classic Welsh landscape of terraced housing clinging to picturesque hillsides”.

But I wasn’t just there just to explore the place. I was there to ‘see’ {150}, the first-ever collaboration between Wales’ two national theatres, the English-language National Theatre Wales and the Welsh-language Theatr Genedlaethol Cymru.

It takes about 4 hours each way to get down to South Wales from the North, an oversized trip just to see a show. But it was a show by Marc Rees, an artist whose generous and engaged approach to art and theatre I very much admire. I was lucky enough to meet him and listen to him talk a month or so ago, at Anwen School at Castell y Bere. The inspiration, the idea, behind all his work is ‘Fy milltir sgwar’, a re-imagining ‘my square mile’. He says the concept of fy milltir sgwar (which is a huge part of welsh culture, and I’m not sure there is an English equivalent) is a “constant source of inspiration, always reinventing itself. When I make work in places beyond my square mile, I take the idea with me, appropriating that space and working with the people connected with it. You can’t just land in a new place and make a show”.

I also like Marc’s approach to the structuring of the work (layering, multi-sensory and so on), developed not least through his links with Brith Cof, and Mike Pearson, who are also pioneering interesting place-based approaches to performance [see my blog on Mike’s book Archaeology/Performance].

Marc had been commissioned to develop a show to mark the 150th anniversary of the 150 (ish) welsh speakers who made an 8,000 mile journey in a boat called Mimosa, to found the colony called Y Wladfa in Patagonia 1865. I’m intrigued by Patagonia, and by how much pride, romanticism, there is about the relationship between Wales and Y Wladfa. It is so different to the shame – is that the right word – of the English about their colonizing past. Why? Is it justified? What would Marc make of it all?

It turned out that the show was a 150-minute visual, auditory, olfactory, tactile marathon. Described by one reviewer as “live documentary: visual vignettes, discomfiting soundscapes and a general mood of playful discombobulation", I loved every minute of it.

We were walking and standing most of the time, and I’ve heard others saying things like ‘it could have been half an hour shorter’. But that was, I think, the point. About 2 hours into the show, it seemed it was coming to an end, but we were moved on again (to a beautiful and poetic ending, but more of that later). Mirroring the second phase of colonisation, moving west to new land.

And I think I now understand the pride and romanticism associated with Y Wladfa. The colony was inspired by Michael D Jones, a preacher from Bala. He’d had a vision of ‘Wales away from Wales’, where the language, culture and traditions of Wales could flourish, free from English influence and oppression. So the primary reason for the colony was not the usual ‘plunder and get rich quick’ (although there was hope that good livings could be made, in contrast to the poverty blighting communities in Wales), but a cultural oasis, driven by oppression at home.

The story is fascinating, including the relationship between the native tribes and the new settlers (which again, is not the usual sad tale of antagonism and destruction). If you missed the recent S4C/BBC2 Huw Edwards programme about it, the story is well summarized in this review of {150} in The Independent

One of the most interesting things about the show, was that in contrast to many of the accounts of historical ‘events’, women, and their stories, ideas and achievements were centre stage. The exploits, bravery and hardiness of men shown as punctuations. The irrigation system that transformed the arid valley into a fertile plain was, for example, a woman’s idea. And women had suffridge in 1902, well before the UK. There was a great bit in the show when a protest by children took place at a mini Eisteddfod (my first!) when it all seemed to be becoming too male centric. The lack of women in (his)tory is something that is on my mind at the moment: I’m currently working on a piece in response to Richard Long’s ‘Blaenau Ffestiniog Circles’ (at the invitation of artist, Marged Pendrell - see more about it here), in which I decided to walk around the town, looking for traces of the women, and in particular traces of evidence to corroborate or refute the terrible reputation of the quarrymen’s wives.

{150} was brought to life with words and recordings and lives of real people. It constantly mixed and questioned past, present and future: multiple video backdrops were often used to bring the past into the present, and question where we were. The picture below was a particular favourite, where the projection of dancing women, gave way to Alan Ginsberg, his poem Wales Visitation (1967).

As well as being intellectually and culturally sophisticated, the show was mesmorising – I don’t really know how to do justice to it. One of the highlights was following an articulated truck into the building at the start of the show into the hangar full of Royal Opera House props and backdrops (itself symbolic of traces of stories and dramas, culture preserved, packed away, far away), and seeing to the sides of the main hangar enormous, pitch black corridors (also full of props) at the end of which you could see watercolour like vignettes of a woman in profile against the landscape outside, in her pastel pink costume and huge hat.

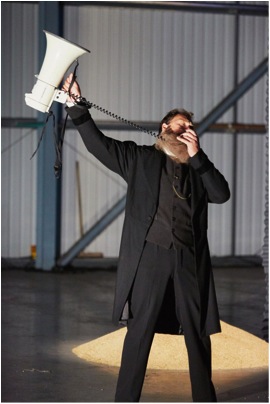

There was some fantastic singing, some amazing performances and lots of little things to notice, like old tape decks, welsh blankets, Marc wearing classic Patagonian trousers, boxes with the names of the 150 people who went on the Mimosa (66 from the village in which the performance was held). Marc’s ‘process’ was also on show, with vignettes of conversations he’d had with locals and collaborators in Patagonia during his research.

The use of straw bales and grains of wheat (at one point, a woman standing on a table poured grains of wheat into my hands from a cosied tea-pot) and the different temperatures in different parts of the building meant that it was as much about smells and feeling as it was visual. It was a full heart – mind – body experience.

It might all have been a bit heavy, but there was laugh-out-loud humour too, in the Eisteddfod tent, naturally and unassumingly performed by children from a local drama group.

Ending a show like this must be tricky, but Marc had it covered. We gathered at the far end of the hangar. We'd got used to the presence of huge opera stage backdrops around the space and the one infront of us appeared to be covered with welsh blankets. When the blankets were torn down, it took a few minutes to realise it wasn’t a backdrop at all, but the view. My friend burst into tears.

The show ends tomorrow.