Lisa Hudson and I are artists, and we have marbles. Dr Jonathan Malarkey is a process scientist, and he has a lab. Rhys Trimble is a poet, and he has a megaphone. And Katherine Betteridge and Sioned Eleri Roberts are musicians, and they have all sorts of instruments. Together, we are going to make something about Llif, /Flow, to show at Bangor’s spanking new theatre, Pontio, on 3rd July.

Quite how we are going to do it, we don’t know yet. Although we have a nugget of an idea that involves linking Jonathan’s research and marbles flowing, inside and outside the Pontio building and the Caban, something that is fun and interactive and curious, that is visually, physically and auditorily experiential. We have 2 ½ months to work it out.

This - Llif/Flow - is our Synthesis project. A pilot project by Pontio to explore of where art and science meet. Elen ap Robert, artistic director at Pontio said, "What can happen in that space between molecules and marimbas, between test tubes and trills? We’re interested in finding out, and this pilot project is an experiment in itself for performers and scientists to form partnerships, adventure beyond their comfort zone and see what exciting and innovative ideas they can develop."

When we met with Elen, Shari Llewellyn and James Goodman, to discuss the project, we were delighted by their interest, enthusiasm and support. Possibly one of the most rewarding meetings I’ve ever had: They welcomed the uncertainty, the experimental nature of it, the fact that this was a completely new collaboration, and (oh the joy!) required minimal bureaucratic forms or processes. They are keen for us to capture our learning along the way, and this blog is the start of that.

Our first step was to visit Jonathan’s lab next to the Menai Straits, on sunny Wednesday this week.

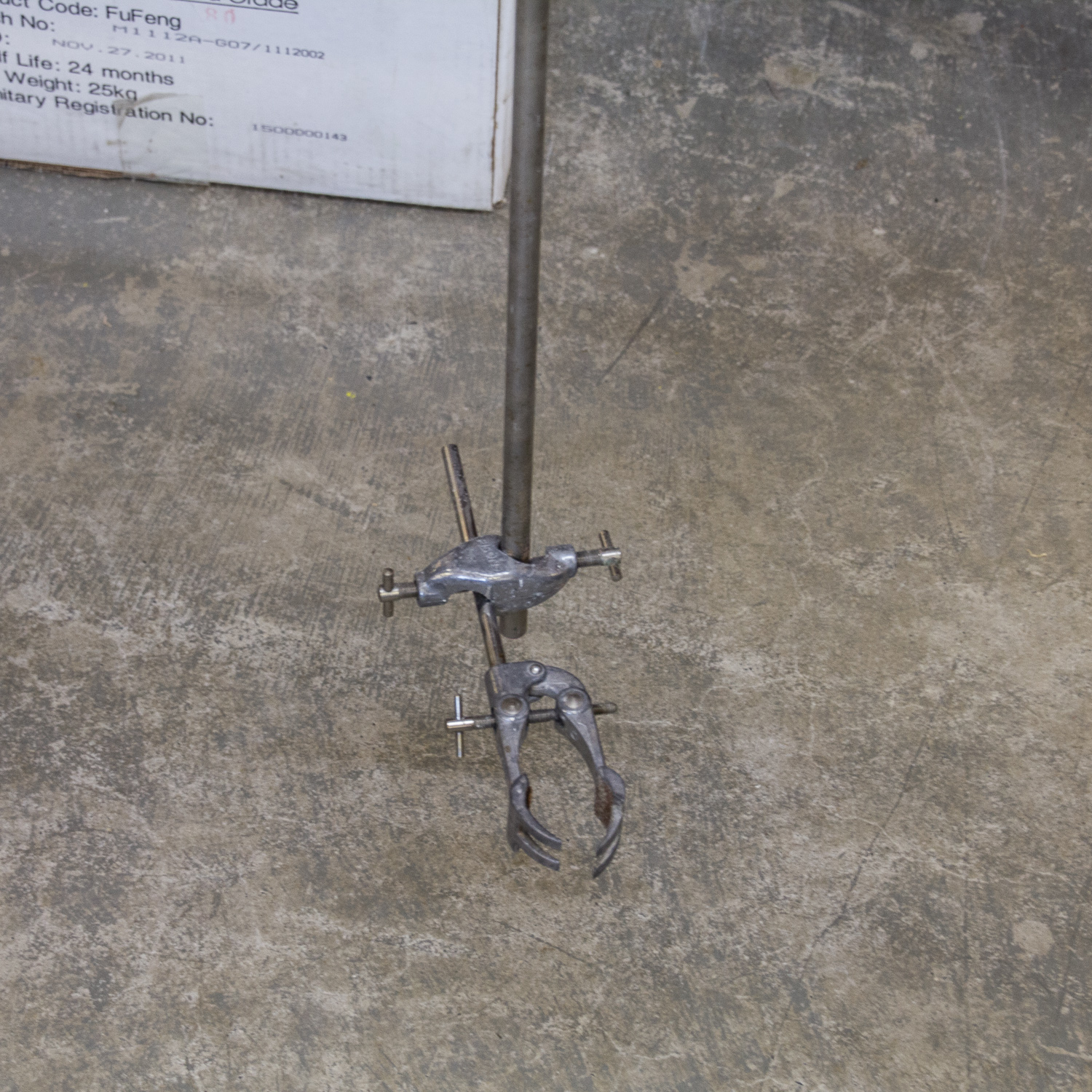

In his lab, Jonathan has a wave machine and a laminar flow table and something that makes waterfalls and something else that makes vortices and many, many buckets of sand and muddy stuff. He also has a concrete mixer, and lots of useful bits of mechanics that are made from stuff they’ve found (like clamps and bricks and bits of metal).

This was something of a surprise, and was Lesson 1: Scientists don’t all have labs that are all white and smell of chemicals, with high tech stuff bought at vast expense. A little ‘Heath Robinson’ is how Lisa described it, with some delight. A tick for communality of approach, as Lisa and I also like to make stuff from things we’ve found. Lisa had brought with her, for example, a marble release mechanism made from pringles tubes. [Note to us: Design board – Lab chic]

Lesson 2 was that although scientists specialize, they are not (necessarily) isolationists. Jonathan is (in his words) “a process scientist – I look at processes related to sediment transport”, and he specializes in the boundary between sediment and water (the Benthic boundary layer). He likes to focus, to reduce uncertainties and complexity, so he can study and understand what is going on. He studies the movement of tiny particles (sand, mud etc) and this might be at a tiny scale of individual ripples in the sand bed but it could also be at bigger scales (in which more ‘real world’ complexity comes in), in particular, estuary-wide.

In Jonathan’s words, “Scientists are just curious about the world”. And although scientists may have finer and finer specialisms, they like to talk to you about their work, and how their insights apply more widely. When we asked Jonathan about this, he said “Well yes, I know about the movement of water”. It turned out to be even wider than that, for example, we got onto the break up of Tacoma’s Narrows bridge in the 1940s, blowing smoke rings, plane aerofoils, droplets landing in water, ripples spreading out in a pond, patterns of flow in rivers… Lisa and I can hardly look anywhere now, or have a conversation, without noticing some variation on the things he’s been telling us about… although I’m sure some connections are spurious. For example, take a look at the second animation on Jonathan’s website here, which shows oscillating flow of water over steep ripples and the shedding of vortices that completely dominate hydrodynamics and sediment sediment transport. It isn’t possible to look at that, in my studio in Nantperis, and not liken it to the weather we experience here between the mountains…

Lesson 3: There is a distracting beauty in science. Equations are beautiful. Terms are beautiful. Here are just a few, to give you a taste:

• Laminar flow • Chaotic flow • Oscillatory flow • Orbital excursion amplitude

• Convective eddy viscosity • Vortex ripples • Nondimensional vorticity contours • Vortex shedding • Attending vortices • Von Karman Vortex Street • Stress harmonics • Turbulence-closure model • Strong second harmonic • First and third harmonic amplitudes of d(u)/dy • Angle of repose • Stagnation point • Phase enabled horizontal velocity • Free-stream velocity • Kinematic viscosity of water • Spilling breaker• Plunging breaker

So while we were at the lab, finding out about Jonathan’s research, learning about a whole new way of looking at and understanding something we’d never really considered before, the beauty of the science, it’s equipment, it’s outputs, the feel of the whole place and the activities and culture there, were quite distracting.

I wanted to listen and photograph and video and sound record. I found myself transfixed by the beauty of the water surface in the wave machine (that looked like a silver banner rippling in the wind), the sound of the waves breaking on the ‘beach’ at the end of the tank, and trying to speak the equations, just to hear what they’d sound like (they are full of lovely little symbols that I have no idea how to articulate). Listening to the recordings has made me realize how much I missed at the time. [Note to self: record all conversations for left brain to engage with at a later date]

Lesson 4: I feel unsure about writing about the ‘content’ of Jonathan’s research. There’s a clear divide between getting a ‘sense’ of it, as an artist, and trying to present it back in a way which is accurate enough to do justice to Jonathan’s work.

I feel a strong need to check it with him first*. But for better or worse, here goes:

Understanding sediment transport processes helps us understand how to make practical predictions in rivers and along coasts (often working with natural processes - eg groins on the beach, for example are not always a good thing, whereas beach nourishment using offshore dredging which does not interrupt the natural flow of sediment is generally a good alternative) in all sorts of contexts

There are different types of flow eg laminar, turbulent, oscillatory, steady, tidal etc

A lot of stuff happens at the Benthic boundary layer, and it is really, really complex, even if you isolate processes down by studying them in a wave tank

Particles move differently under different types of waves, at different depths and under different parts of waves. Simultaneously, some will be moving backwards and forwards, others up and down, others in circles. Things like wavelength, how deep the water is, whether the wave is being dissipated on a shore, how fast the waves are moving will have an effect on the resulting patterns in the ripple bed, and all these things can be modeled and predicted very pretty animations and equations

The shape of the ripples on a bed will be different depending on whether they are (mostly) from wave or current action. They have an angle of repose and when you watch them, their surfaces are jumping with little particles, almost like fleas, and that is the way the ripple is moving (eg typically towards the beach for a wave or in the current direction for a current)

Vortices are critically important, perhaps THE most important influence on what it happening [see the plethora of example terms in Lesson 3]. In fact, these vortices – and often how to avoid them - have an effect on lots of things (from the design of a golf ball to design of suspension bridges to the collection of seaweed on the ocean surface). Quite often, they are not considered in the design phase of something, and that can lead to problems (eg have you noticed some cars make a terrible eardrum-breaking wah wah wah noise when you wind a window down a certain amount, and some don’t?).

[* Did check it – couldn't help myself! Many helpful corrections and clarifications, much adding of "processes", and the comment "Not bad. It looks like you took something in"]

Lesson 5: Art and science are both ways of exploring, enquiring and being curious. The question is how do they meet? Or perhaps meet is not the best term, how can one can ‘riff’ from the other? I’ve noticed at least 4 ways so far…

Using marbles to illustrate, explore and experience (an approximation of – an analogy to?) the science of flow: what goes on in vortices, in different characteristics and types of flow, sediment transport etc

Using scientific methods (plotting, mapping etc) to explore, experience and better understand the behaviour (flow) of moving marbles

Exploring (illustrate, draw attention to, create from) everyday opportunities to see and experience flow

Abstracting from the science of flow and/or marbles, using artistic responses in sound, poetry, physical and visual works….

I suspect that between us, we’re already looking into all of these. It’ll be interesting seeing where they go, which translate best into making a ‘show’ on 3rd July.

So, in conclusion….

Once you find out about this stuff, you see it everywhere. It changes how you experience the world. Rather than take out any of the wonder, it just makes you look more deeply. I have heard artists say that it is best not to know too much, not to know the names of things, or become an expert in something. Well there is no chance of becoming expert (this stuff is mind poppingly complex), but I think I could probably now spot a stagnation point, a vortex and could distinguish current vs wave-caused ripples in the sand. See here for example, ripples oscified in rock, 500 million years old that I saw on a walk on Carnedd y Filiast a few weeks ago....

.... and the mudflats at the mouth of the Menai Straits (on the same walk)...

We don’t know yet how exactly this will relate to our marbles. But our next day together will be to visit my studio in the barn, and play with marbles. And anyway, if we did, where would be the fun in that? As Jonathan said in an email “At the pop-up museum [see Digging Down], I had an interesting chat with Marged and she said that the uncertainty was a good place to be in as an artist, so I will just have to get used to that”.

An afterthought: Maybe I’m over-generalising – Jonathan is perhaps not typical of all scientists. I suspect he is particularly perfect for this project!