"To find a form that accommodates the mess, that is the task of the artist now" Samuel Beckett

Amser maith yn ôl, a long, long, long time ago, lava squirmed up in the bottom of the sea, in a corner of the world. Black smokers on a massive bed of sulphide ore, with a pretty Ordovician border and a practical Rhyolitic cover. Cosy in its layering, it travelled on many journeys, from the Llandovery epoch across the lovely (for it was surely lovely) Iapetus sea, crinkling and crumpling, riding up to form a new land. Within that land, a mountain arose, exposing its folded body. Small in stature (for Eryri was to be nearby) but acid house coloured with the complexity and concentration and scars of its formation.

Many years later, many, many years, (wo)man came. (S)he saw the mountain and called it lovely and gave it names like Mynydd Trysglwyn (which is thought to mean a hillside covered in a thick grove of rough trees covered with scaly lichen growth), and then they called it Mynydd Parys and Copper Mountain, and always the names were mountainous, despite its limited stature. (Wo)man befriended it and got to know it intimately.

Bard (Rhys Trimble) ar y top. Mountains of Snowdonia behind, across Anglesey plain and the Menai Straights

Arlunydd, artist (Lisa Hudson) ar y gwaelod

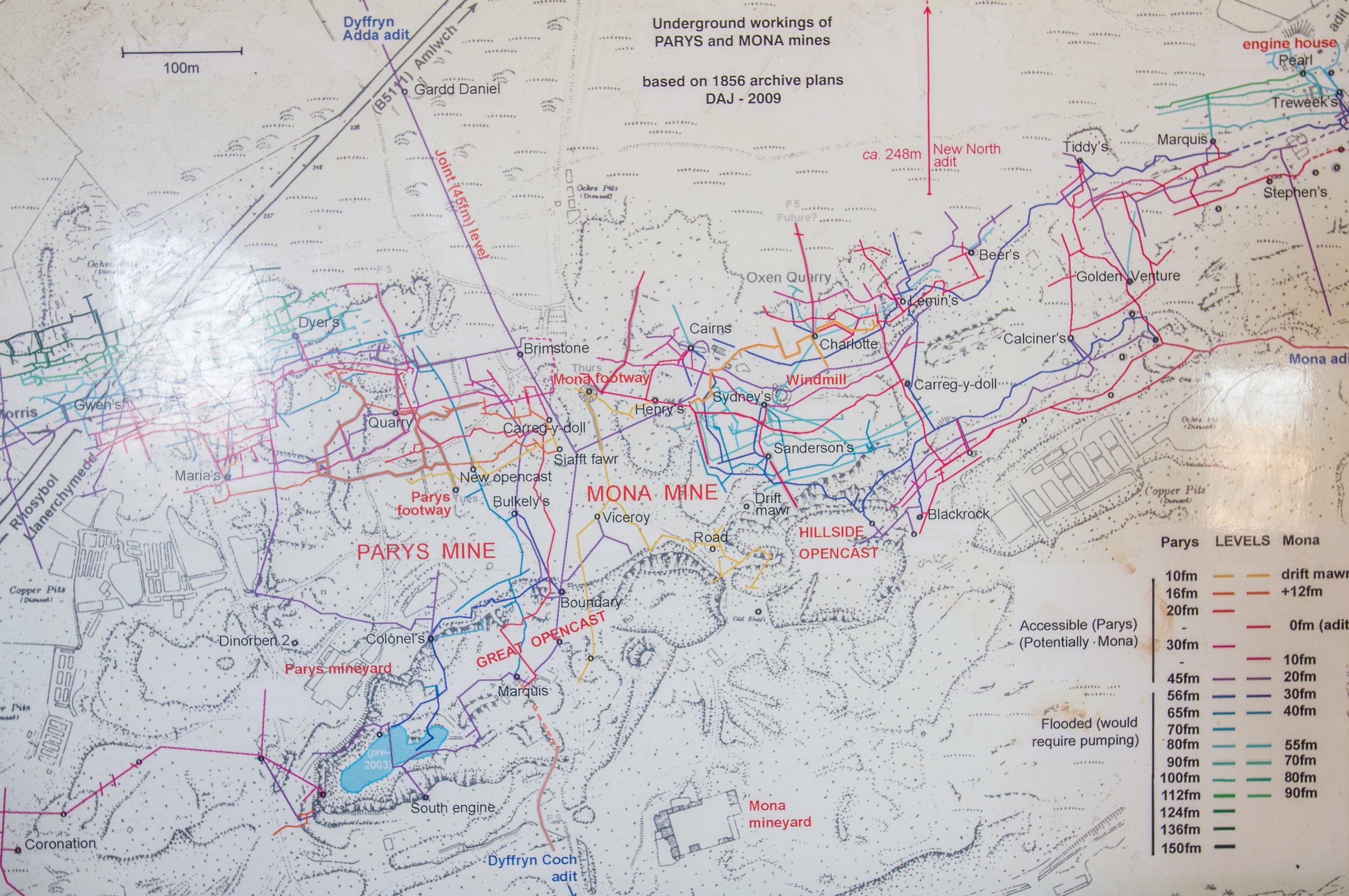

So intimately did they want to know it, that they dug down and brrrowed in, extracting and examining piece by piece. They couldn't stop. Plundered, eaten and honeycombed. There was copper, and gold and silver and lead and aluminium. Bronze Age, Romans, Tudors, Roland Puw, Cornish, Industrialists, the Marquis of Anglesey andAnglesey Mining PLC. The men, the children and Copper Ladies. These Copper Ladies broke up the mountain ore and “wore a Jim Crowe hat under which a spotted handkerchief covered the head, neck and most of the face. The fingers and thumb of the left hand were cased in strong iron tubes forming a sort of glove.” (There is much more to the story, and it's brillantly described by the Parys Underground Group.

Later, man mapped it in cores and put it in the pattern shed. The patterns shed burnt down. They mapped it on computers and asked for reinvestment. Not enough.

Periods of quiet.

Women and men. Hungry for resources. They dug down and Burrowed into it, reverberated it and precipitated it. Cloddfa Parys. Cloddfa Mona. Water collected in the tunnels.

As the water grew, the mountain gave birth to its first river, so. Dyffryn Adda. River Adam. Running red. Then call it Yr Afon Goch. The Red River. " Vitriolic liquors" flowed out of the mountain, and "taken for ulcers, itches, internal haemorrhaging, worms and diarrhoea". A Dam, later. The mountain filled with frustration. It ate cars in half, and pots and pans and shopping trolleys.

CuSO4 + Fe → FeSO4 + Cu

Rust turned to copper. Alchemy. Great precipitation pools were made, daisy-chaining the slopes, to harvest the waters.

A long time ago, they said of this: "In plain English a quantity of iron must be immersed in the water. The kind of iron is of no moment; old pots, hoops, anchors or any refuse will suffice... These they immerse into the pits; the particles of copper instantly are precipitated by the iron and the iron is gradually dissolved into the yellow ochre; great parts of it float off by the water and sinks to the bottom. The old iron is frequently taken out, and the copper scraped off; and this is repeated till the whole of the iron is consumed..horse shoes, iron made in shapes of hearts and other forms are put in the foreign waters and when apparently transmuted, are given as presents to curious strangers."

People say it still works now. Nails in the water turned to shiny copper plated. But alchemy is fickle. Curious strangers, two artists, two scientists, two musicians and a poet, found that 8m of thick galvanised steel disappeared in the waters, after 3 weeks, leaving Tirlun Afon Goch, Red River Landscape.

14 years before we witnessed this dramatic event, the modern world had come to Mynydd Parys and David Jenkins had found the dam. And he found that it was old. The towering body of water water ate at it. Sulphuric acid. Ph2. Amlwch, village sat in the marsh around the strangled river shook in fear. A sword of Damocles.

They decided to drain the mountain.

Dave Johnston of Natural Resources Wales and Prof Paul Younger of Glasgow University and the man in the kiosk at Amlwch port are all able to tell the tale of the draining. It is a dramatic story. More than 5x the amount, beyond their wildest concerns. Calculations had been made. No one expected the 270000m3 nor the 3 weeks of pumping required. Rubber gloves, boots and pumping machinery sacrificed. Dramatic. Disturbed locals. Turbulent.

And now the red river runs gently, but let it not be forgotten that this is Britains most polluted acid mine drainage, running along its length from clear to red to milky pink. Straight into the ocean (through an old Bromide factory). No signs to say this will eat you up. No money to cleanse or harvest. People know to keep clear. Only bacterial blooms shade in the waters.

And so the story ends (or this chapter of it) in a tower at y 'Steddfod Genedlaethol, Bodedern, Ynys Môn. Yn Troelli, curated by Manon Awst, a creative laboratory in which she is "reconsidering landscape within the context of the controversial debate concerning the ‘Anthropocene’ – the term proposed for the new geological epoch which acknowledges the far reaching influence ofhuman activity on the Earth. ‘Here’s an opportunity,” says Manon Awst, “to inspire the Eiseddfod audience to reconsider their relationship with the ground beneath their feet, and to look afresh at the environment around them – the land, the sea and the atmosphere".

Llif Labordy Môn, in a Tower (with marbles) - observation, extraction and transmission, like science, like art.

Darlith perfformiad - performance lecture, Awst 10 August 1 - 3pm.

With thanks to Pontio and Synthesis for their support.