September started for me in Kintyre, in a little place called Saddell. There’s a castle and a row of little (and not so little) houses along the coast that were all part of the Saddell Estate, now owned by the Landmark Trust.

Our place was right at the end, and called Cul-Na-Shee. It was built originally for a retired school mistress (great term), with its toes in the shingle, looking out at that view above, across some extraordinarily diverse and beautiful (and ancient) rocks, the Kilbrannan Sound, and towards Arran.

“ The house, even more than the landscape is a ‘psychic state’, even when reproduced as it appears from the outside, it bespeaks intimacy” - Gaston Bachelard

I was there on holiday. with my husband, Ed Straw, and friends - artists Jony Easterby and Pippa Taylor. And we busied ourselves doing as little as possible. I had deliberately not brought my ‘proper’ camera, and leisurely went about playing with drawing and mapping - trying out ways of mapping a place that I don’t know very well, but that I’d come to know a little better over the week.

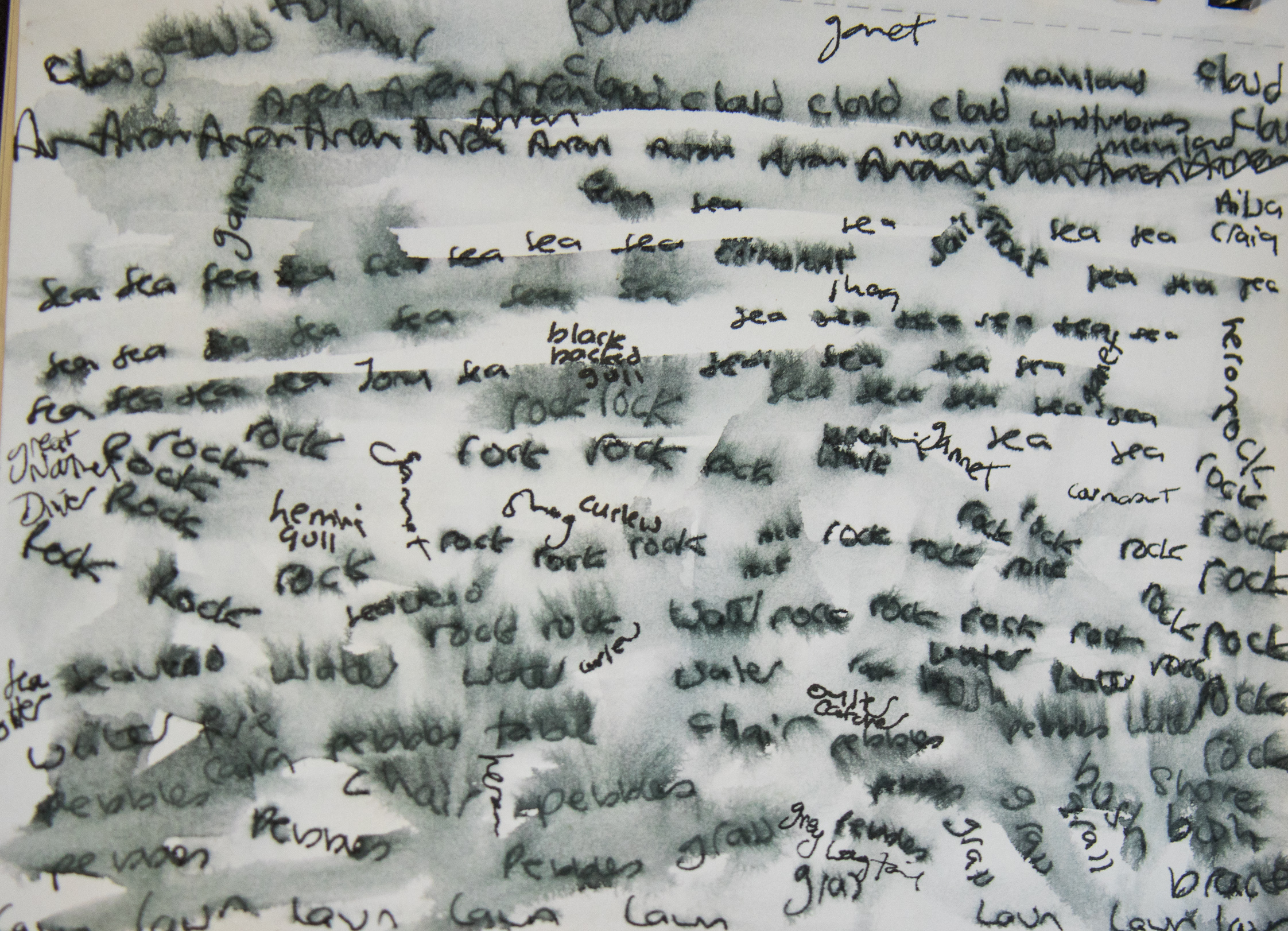

I started with the view, and some Scots words:

Hallyoch - the sound of water over stones

Haar - mist

Wadder - weather

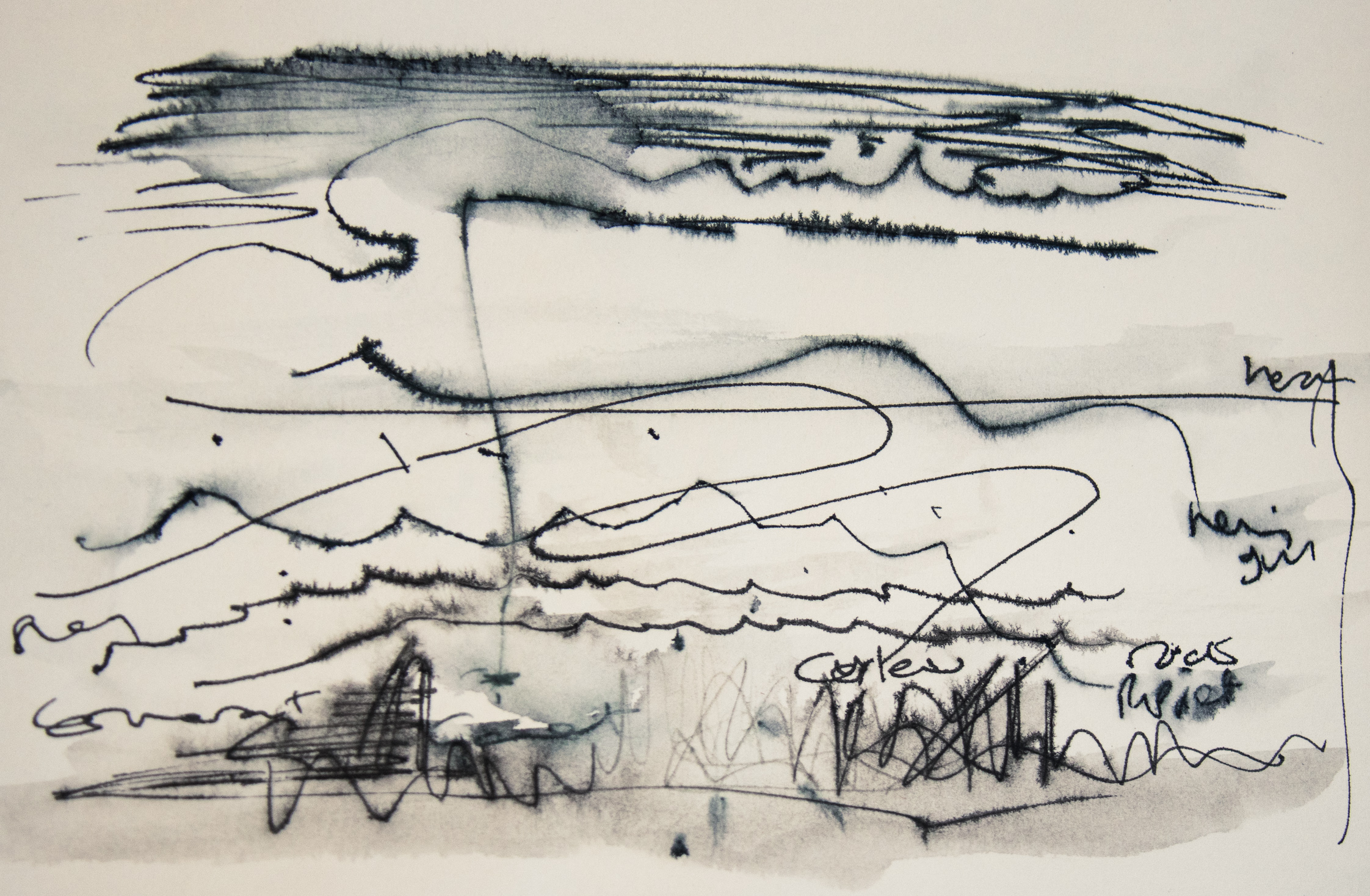

The view encompassed the long and short and fleeting. Along with the long view, I became obsessed with the short. Specifically with the pebbles. There was grandeur in both, as Bachelard says:

“The miniscule, a narrow gate, opens up an entire world. Minature is one of the refuges of greatness”

And they are fractal: minatures of the great beyond. Justifying a growing pebble collection (everyone was very tolerant), and in honour of their greatness, I started making maps of them. (If you click on the images below, they’ll pop up bigger).

I’d been finding mapping for our Merched Chwarel project quite tricky (see Merched Chwarel for our maps in progress), so I thought this was a very relaxed place to experiment. I didn’t really want to make maps that anyone could follow. They are more toying with time: thinking of the mindblowing journey of the pebble itself (have you read “The Planet in a Pebble”?), and of fleeting moments, squalls and the lifetime of a footprint.

But I did make a map for how to find my favourite stone, which I’d lost while taking it for a walk along the beach.

I was surprised by the strength of my drive to ownership and hunting, and finding the overlooked. Of hunting and owning the overlooked. I convinced myself that no-one has looked at THAT stone in 1 billion years of its existence - at least not in do much detail.

I pocketed a few.

And then a few more.

I drew the clouds.

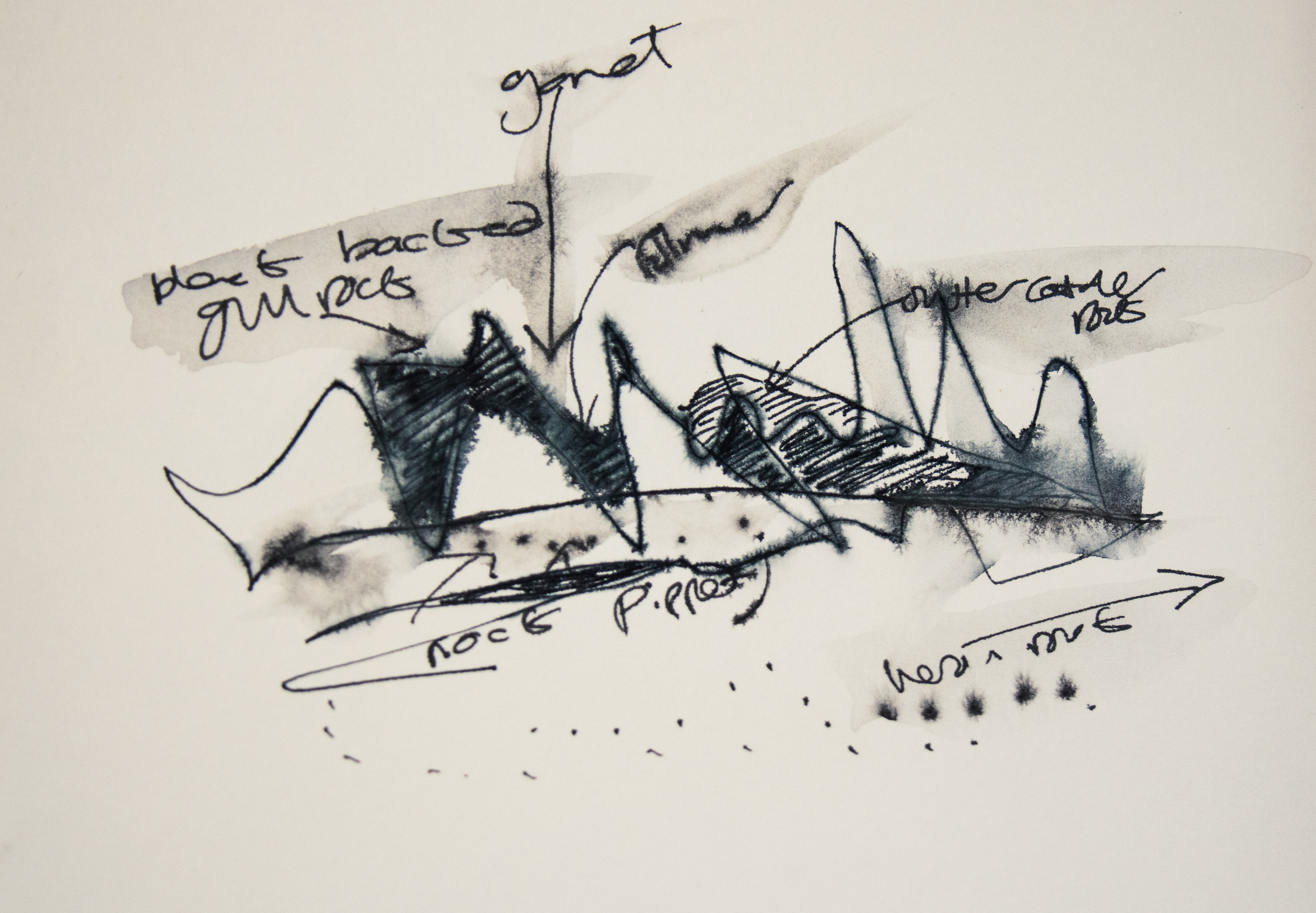

I started naming places according to the birds. They had habits. And favourite rocks. And their flight paths were distinctive. Eyes and ears tired from looking and listening.

On the last night, I made a list of all the species of birds (42) in the visitor book. A sort of map for others. A map of what to look out for. I included the sea otter. It felt a bit uncomfortably like trying to make some claim to the place, so I wrote quite small and possibly illegibly.

Langourie - yearning

Fremmit- foreign

My maps didn’t include the landmarks: the Gormley (the “Warrior”, commissioned for Landmark Trust’s 50th birthday - the same year as mine - was perched on a nearby rock), or the castle, or of piles of stones that other people had made. These felt like they were claiming the space for those who had made it, and I thought of “Plop Art” - ‘public art’ in people’s Milltir Sgwar. No wonder people react strongly to them. Who are we, to come in, and do this, to a place to which others belong?

Instead, I mapped the route to Treasure Island, a place I canoed to along the coast, along the line of lobster pots… and beyond. I pulled in at a little shingly beach between the treacherous looking spikey black rocks, and walked back to the things I’d seen as I’d canoed past. Here I found I could convince myself noone has really been there before, or had never got that far before, or for that long, or looked in that detail. It wasn’t in fact, an island. But it had Henry Moore sculptured rocks and perfect rock pools and Sea Urchin shells. And there was a tall, ferny, orange-coloured waterfall, large bright bits of industrial plastic things. I pocketed the sea urchin and another rock. My map includes the treasure I brought back.

Voar- spring

Hurlygush - the sound made by falling water

Glöd - sunshine

I pocketed the sea urchin. And another rock, well three, but I left two behind at Cul-Na-Shee.

The others could have followed this map, but they didn’t.

Instead, Jony went out to sea and caught some mackerel, while the shore was lined with men seeking to catch sea trout, accompanied by the Gormley (that island in the distance to the right is Aila Craig, with rock so hard it is used to make Hurling stones). Pippa composed a tune to Cul Na Shee. Ed walked up a mountain.

Having failed to find anyone willing to follow my maps, I made a map for myself, using OS maps, my igeology app, and a book about the History of Campbelltown, to find the quarries of the area. Of which there are a remarkable number, and I presume almost entirely disregarded. Surely no-one else has plotted their walk to take in the quarries? Here I was, Merch y Chwarel ar wyliau!

Ling - patch of heather

Doited stores: crazy cattle

Rather to my surprise, the maps worked.

The quarries were small, domestic, possibly built for making the houses. I pocketed some quarry rocks - blocky and red. They look useful, the sort of thing that would be quarried. The whole landscape was being put to use, and had been for generations: farming (sheep and some mad bullocks), horses, conifer plantations, hydro schemes. Quarries. The only wildness, really, was out to sea.

I got my husband to take photos of me being in quarries. I think I may send them to my fellow Merched Chwarel, as postcards.